Don't be a Coco, be a Christian

The style of resistance.

Last Saturday’s No Kings March — held the same day as our president’s birthday, err, sorry, the 250th anniversary of the U.S. Army — set up a stark divide, once again, between two types of Americans: G.O.P. Republicans vs U.S. Patriots.

The “birthday parade,” which cost U.S. taxpayers $45 million and featured armored tanks (to include one especially squeaky one), helicopters, historical military equipment, 6,000 uniformed soldiers, 34 horses, two mules, and one dog, all marched down Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C.

Major conflicts in history were “re-staged,” including the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Gulf War. Soldiers dressed in period military costumes, some of which were even rented and shipped in from Hollywood.

I happened to be in Washington a few days before the “festivities”, and since my hotel was just three blocks from The White House, I was sickeningly privy to the pre-parade preparations. I watched government employees put up fencing, install sidewalk barriers, and construct the viewing stands on Constitution Avenue (“Constitution Avenue!”), so Trump and his craven cronies could soon lord over and “review” these American assets on Saturday June 14.

The whole city was uncomfortably on guard in the lead up, ready to be besieged by the MAGA faithful in town from places like Pennsylvania and Ohio, as the White House bragged the event would draw 250,000-300,000 attendees.

Yet attendance for the parade lost steam in the final days and you could weirdly feel it. Ads were even spotted on Craigslist late last week, offering a “flat fee of $1,000 paid in cryptocurrency” to anyone willing to sit in as yet unclaimed parade seats. The offer came with a “free fast-food lunch,” and instructions to wear red hats and gold accessories.

Saturday July 14, 2024 arrived. And attendance at the toddler’s birthday tantrum was teeny tiny.

But you know who did show up for our country on the exact same day?

Americans in the millions and millions turned out en masse in communities across the country this past Saturday, raucously pushing back on President Trump’s authoritarianism, attacks on immigrants and LGBTQIA+ rights, and unspeakable cuts to scores of federal agencies and programs.

Nonviolent protests are twice as likely to succeed as armed conflicts. The 3.5% rule is a concept in political science that when 3.5% of the population of a country protests non-violently against a government power, that government is likely to fall from power. The People’s Power campaign against the Marcos regime in the Philippines (which drew two million protestors at its height), the Brazilian uprising in 1984 and 1985 (which drew one million), and the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia in 1989 (which drew 500,000 protestors) are examples of the success of this concept.

The June 14 “No Kings” protests are now thought to be the largest in U.S. history, making them a critical building block toward the 3.5% rule. A glimmer of hope? Yes.

But there are still waaaaaaay too many among us who traded their souls- and still side with a racist, fascist regime, and a would-be dictator. These Americans appear not to care at all that future generations will judge them, abominably, and God willing soon.

And since the arc of history bends toward justice — but only if we bend it ourselves — let’s turn back the pages of fashion history to reflect on the decisions made by none other than Coco Chanel and Christian Dior in the years before, during, and after WWII. Two iconic designers, two contrasting courses of action, two different permanent legacies.

Coco Chanel embodies what not to do, who not to be when existentially tested. Christian Dior instead models uncommon courage, quiet grace, and a deep commitment to the power of fashion.

COCO CHANEL

How it started:

Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel was born the second of six children in a “poor house hospice” in Saumur, Maine-et-Loire in western France. At age eleven, when her mother died, her father sent the boys off to work as farm laborers and sent the girls to an orphanage run by the Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Mary at the convent of Aubazine. The setting was a stark, strict one for Gabrielle, but it was here that she learned to sew.

How it went:

Coco Chanel became a master of self-invention, and her imagination was boundless. In the 1910s, she began to design clothes with simple lines in comfortable jersey fabric, at that time freeing women from their corsets. And she also gave the world the little black dress. I mean, the little black dress!

She founded the Chanel brand, was credited post-WWI with popularizing a sporty, casual quality of chic on the forward edge of women’s style, and she also extended her influence beyond clothing; into jewelry, handbags, and fragrance. Her signature Chanel No. 5 perfume remains iconic the world over, as does the interlocked-CC monogram she designed in the 1920s.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Chanel closed down her fashion house, stayed in France during the Nazi German occupation — and collaborated with the occupiers. Declassified documents unearthed by journalist Hal Vaughan reveal that she collaborated directly with the Nazi intelligence service, the Sicherheitsdienst.

Coco Chanel worked for General Walter Schellenberg, chief of the “SS” intelligence agency. She acted as a key envoy, making trips to Madrid and London, to deliver messages from the S.S. to major figures like Winston Churchill. (At the end of the war, General Walter Schellenberg was tried by the Nuremberg Military Tribunal, and sentenced to six years of imprisonment for war crimes).

Motivated by self-interest, and antisemitism, Coco Chanel also used the war to seek financial opportunity for herself. Citing the Nazi and Vichy anti-Jewish legislation which brought with it the seizure of all Jewish owned property and business enterprises, she tried to wrest complete control of Chanel No. 5 from her Jewish business partners. Chanel used her position as an "Aryan” to petition German officials to seize sole ownership.

Unaware that her business partners, Pierre and Paul Wertheimer, had anticipated the forthcoming Nazi mandates against Jews, and taken steps to protect their interests she was ultimately unsuccessful, thankfully. Since prior to fleeing France for New York in 1940, the Wertheimers had turned legal control of “Perfums Chanel” over to a Christian, the French business man and industrialist Félix Amiot. At the war’s end, Amiot turned “Perfums Chanel” back over to the Wertheimers.

How it ended:

In September 1944, Chanel was interrogated by the Free French Purge Committee, the épuration légale, about her Nazi ties. Soon after, she fled to Switzerland to avoid criminal charges for her collaborations as a Nazi spy.

Chanel was believed to have eventually been pardoned behind the scenes thanks to Winston Churchill, and in 1956 she re-opened her fashion house. She went on to even greater fashion fame and fortune, but if you Google, almost every account of Coco Chanel’s life addresses her active involvement in the work of the Nazis.

Her legacy fashion house remains one of the world’s greats, but her actions and alignments before, during, and right after World War II will never be forgotten.

CHRISTIAN DIOR

How it started:

Christian Dior was born in Granville, France and was the second of five children of Maurice Dior, a wealthy fertilizer manufacturer (the family firm was Dior Frères) and his wife Madeleine. His family hoped he would grow up to be a diplomat, but Christian Dior was much more interested in art.

In 1928, Christian Dior left school to open an art gallery which sold works by Pablo Picasso among others, and he went on to cultivate friendships with Picasso, Salvador Dali, Jean Cocteau, and Alberto Giacometti. Dior was forced to close the gallery three years later, when his mother died and his family experienced financial trouble during the Great Depression.

In search of work, Dior created and sold fashion sketches, some of which were eventually discovered by fashion designer Robert Piguet. From 1937, Dior was employed by Piguet, who paid him to design for three separate collections.

Some time after, Dior was called to serve in the French Army, but when he returned he joined the fashion house of Lucien Lelong. For the duration of WWII, Christian and his team of employees (who Christian hired to assist him) designed dresses for the wives of Nazi officers and French collaborators, as did other French fashion houses that remained open during the war; to include Jean Patou, Jeanne Lanvin, and Nina Ricci. Christian Dior was never openly supportive of the Nazi regime, he instead put his head down and worked.

How it went:

Christian Dior forged his own path in France during World War II. He was steadfastly loyal to France. His income kept his family’s head above water- and he made sure his employees could also pay the rent and keep food on the table.

Christian’s work critically contributed to preserving the French fashion industry during WWII, to keep it alive. And last but not least, Christian financially supported his younger sister Catherine’s efforts as a member of the French resistance.

Catherine ran her underground meetings from Christian’s apartment, and things went well for a while. Until she was arrested and tortured by the Gestapo in 1944. The Nazis dispatched her to a French prison and later to concentration camps: Ravensbrück, Torgau, Abteroda, and Markkleeberg. Christian tried desperately to fund and arrange her release. As the Allies approached, remaining prisoners were sent on a death march, but Catherine managed to escape and return to Paris.

Christian played the long game. He understood that not everyone’s role in the resistance was that of a revolutionary. He understood that victory is often won in the shadows, and in the corners of creativity. He kept his business open during the war to keep everyone around him alive, and to fund the French resistance.

How it ended:

After the war, Catherine Dior went on to testify against her torturers, and was awarded several medals for bravery: the Legion of Honor, the Croix de Guerre, the Combatant’s Cross, and the King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom.

For his part, Christian Dior described maintaining the tradition of fashion as an “act of faith,” a way to preserve the mystery and beauty that fashion brings to society. Dior believed fashion was much more than clothing, it was an art form and expression of French culture.

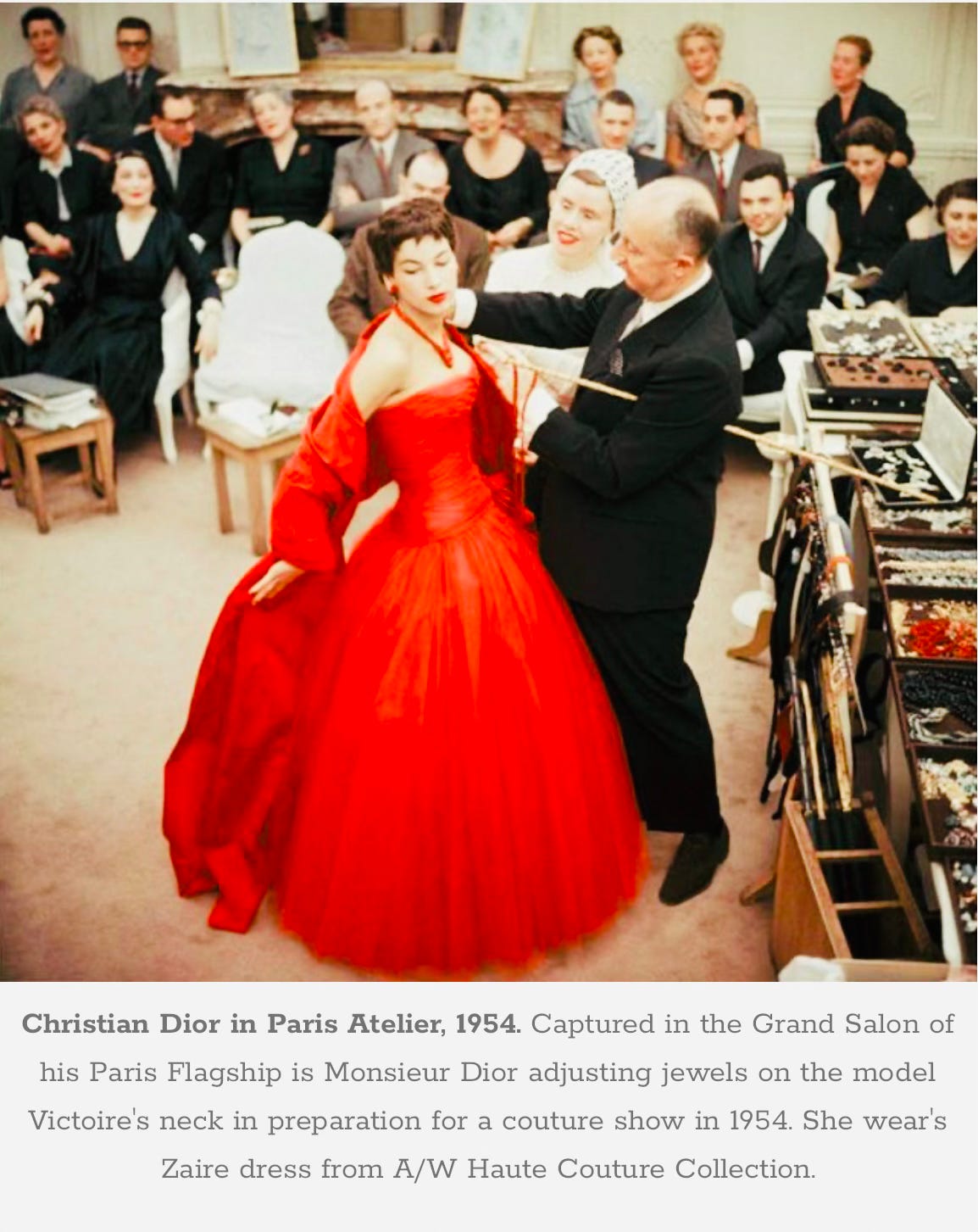

In 1946, Christian founded his house Christian Dior and presented his first collection on February 12, 1947. He called the collection Corolle (circle of petal flowers in English) and Harper’s Bazaar’s legendary fashion editor Carmel Snow instantly dubbed it “The New Look.”

The New Look revolutionized women’s dress, reestablished Paris as the center of the fashion world after World War II, and made Dior an arbiter of fashion until his death in 1957.

And Christian Dior’s fragrance “Miss Dior”— almost as iconic as Chanel No. 5 — is thought to have been named for his sister Catherine.

In summary:

As some in the U.S. now begin to go “revisionist” (suddenly denying that they voted for him, or just now deciding they can no longer “support his policies”), each of us must always hold these Republican voters to account for their decision making last November.

And…

What I’m Reading This Week

Steve Schmidt’s Love and courage will defeat Trump.

“More than anything else, the test at hand for the American people is a moral one. The issues at hand are about right and wrong.

After a long languid season of progress and peace the ground has quaked, and the furies have woken…Let us be honest. Trump has thrown the whole world out of balance. He has disrupted the peace of the world. What are we to do?

The lines between decency and indecency have become blurred in America. We have lost sight of the difference between toughness and cruelty, and because we are a government of the people, by the people, and for the people we have lost connection to the purpose of our nation.

Many of you ask, ‘What can I do?” The answer is simple. You must act.